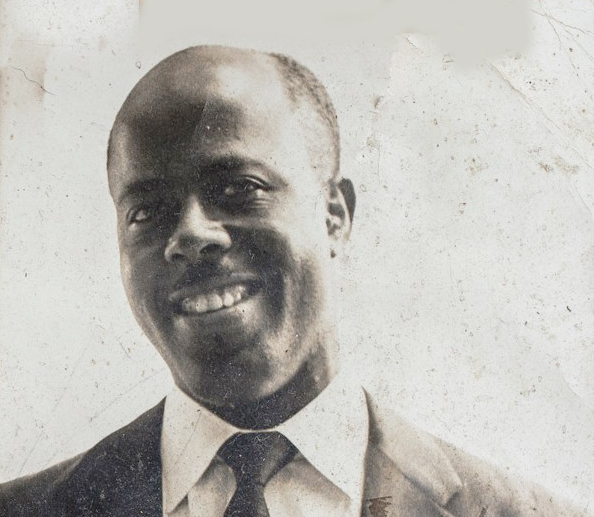

Picture above: John Rivers in his 20s. He was assistant to Neil Humphrey Sr., the first Sarasota NAACP president, then succeeded Humphrey as leader of the organization.

Posted Jun 27, 2016 at 12:01 AM By Vickie Oldham, Guest Columnist

The recently completed “Newtown Alive” history report is filled with examples of the courage, dignity and determination of African-American residents and newcomers who arrived in Sarasota, saw work to be done, rolled up their sleeves and began leading community transformation. The document captures their recollections and testimonies.

Over the last eight months, a gold mine of surprising finds surfaced during research of the City of Sarasota’s Newtown Conservation Historic District project. Watercolor images of Newtown and Overtown, family photographs, maps, memorabilia and audio recordings – rarely seen or heard – were found in private collections. The final report reveals a robust, rich history informed by over 200 primary and secondary source documents, 46 oral history interviews, and the identification of 151 historic structures as well as a set of potential historic districts.

For me, one of the most interesting themes that emerged from the research was the youthful age of Newtown’s leaders who upended Jim Crow laws that blocked equal access to Sarasota banks, restaurants, downtown shops, the hospital, libraries, and schools. The creative, bold actions and persistence of residents such as Neil Humphrey, Jack and Mary Emma Jones, John Rivers, Fannie McDugle, Dr. Edward James, II, William Jackson, James Logan, Bud Thomas, Fredd Atkins, Walter Gilbert, Betty Johnson, Sheila Sanders and many others were extraordinary.

These leaders are now considered community pioneers and trailblazers, but it was as young people that they began shaping Newtown’s future, and inspiring others to move the needle of community progress.

Retired educator Dorothye Smith recalls Edward James asking many questions in second grade. “He always asked ‘why’ about everything,” she said. So as a Florida A&M University college freshman home on Christmas break in 1957, the first question he asked was “why?” when a librarian denied him and three classmates the right to check out books. Undeterred, James kept asking until a meeting was arranged on the spot with Sarasota City Manager Ken Thompson.

FACTS

Newtown Conservation Historic District community presentation

6 p.m., Thursday, June 30

Sarasota City Hall

Sarasota Media Center

1565 First Street

Free to the public;

no reservation required

The college student’s tenacity opened library services to Newtown residents and students. Today, Dr. Edward James II continues to stand in the gap, insisting on positive change and resisting the status quo.

As a 26-year-old on staff at the library, Betty Johnson advanced James’ efforts by working behind the scenes, persuading her bosses at the main library to open a reading room in Newtown. Her idea morphed into a library outreach program that eventually led to the construction of the North Sarasota Public library.

As a 12-year old, Walter Gilbert attended NAACP meetings with his mother and was inspired by local NAACP president Neil Humphrey. “I thought he was a meek man. But his persona changed in my face. I wanted to be a leader like him,” said Gilbert, who at 25 became an NAACP member. Gilbert was mentored by NAACP president Rivers and board member Edward James, then later became the NAACP’s president from 1981 to 1985.

In third grade, Sheila Sanders and her classmates saved pennies, nickels and dimes to learn about money management. They deposited the coins in passbook savings accounts. When Sarasota Federal Bank would not allow African-American students to tour the facility and vault like other district students, Sanders persuaded her 8- and 9-year-old classmates to close their accounts and open up new ones at the Palmer Bank.

As a teen, she routinely studied the agenda of the Sarasota County School Board and rode a city bus to attend the meetings. Years later, Sanders became Gilbert’s campaign manager during his first bid for city commissioner. The team of James, Jackson, Sanders, Gilbert and Atkins made sure that Newtown in District 1 would have representation on the City Commission through a federal lawsuit that they filed and won.

Growing up in Newtown, I knew about the community leaders’ work, but realized during this project the youthful age in which they changed community history. The stories of Newtown residents, told in their own words coupled with documents and photos, paint a complete picture of how young people shaped one of Sarasota’s oldest communities.

Education, exposure, civic engagement and mentoring prepared the young adults for leadership. The same components can transform, inspire and energize today’s millennials to lead.

Vickie Oldham is the Newtown Conservation Historic District consultant and a higher education marketing and communications strategist.